ACEs & PCEs “Nuggets” from Dr. Dean Moshofsky, Pediatrician at Metropolitan Pediatrics.

As I wind down my career, I am looking for ways to make a lasting contribution to Metro Peds. It has been a long and wonderful journey after 35 years and I want to end well. The work we are doing with trauma-informed care and resilience was ground-breaking when we started it in 2015. It is rewarding to see that our local work is now being reinforced with national programs and organizations that have put these topics at the forefront of state-of-the-art pediatric care.

In my last year as a PCP, I would like to give my partners the framework of a trauma and resilience master course. In the same way that I introduced the 2021 AAP NCE Nuggets last year through weekly emails, I will present this information gradually, in bite-sized pieces, with the opportunity for deeper dives for those that wish to study it more in depth.

The topics will utilize the outline from the book Childhood Trauma and Resilience written by Heather Forkey, MD. I will supplement this material with evidence-based studies and material gleaned over my 8 years of studying trauma.

Each week I will present some “Nuggets” as a summary of the topics. Attached to the emails will be supplemental information for a deeper dive. As always, I welcome feedback and responses.

Enjoy,

Dean

Building the Resilient Child

- Understanding trauma is the foundation for providing trauma-informed care.

- Promoting resilience through the building of healthy relationships is the key to addressing trauma.

- Resilience-building works therapeutically by healing the impact of trauma and toxic stress.

- Resilience-building works preventively, in the same manner that a vaccine works.

- Building strength and resilience gradually, with booster doses over time, allows one to overcome traumatic stress and prevent long term consequences of the trauma.

- Our job as pediatricians is utilizing the therapeutic tool of tending relationships. Though the concept to pediatricians is obvious, this work is not easy.

“The skills of resilience-building need to be taught, practiced, refined and reinforced.”

Heather Forkey, MD

Here you can find the Power Point to a talk I gave to Washington County Early Childhood Education workers. The notes on each slide provide more detail. Slides 1-17 give a good summary of CHA’s journey in resilience-building.

Brain Development

- We now know that nature and nurture are both important in brain development. The relationship between the two is dynamic.

- Brain development can be negatively affected by:

- Prenatal nutrition, toxins, infection, and maternal stress hormones.

- Postnatal exposures, family stress, violence, social determinants (food, housing, poverty, etc.).

- Early Brain Development

- The brain is constructed over time in an ongoing process beginning before birth and continuing into adulthood.

- It is built from the bottom up, from simpler lower-level brain structures to more intricate and complex higher-level.

- The ongoing interaction between the genetic blueprint and environment determine which genes are expressed or not, and this, in turn, determines the evolving architecture of the brain – which structures are built, what neuronal connections are made, how and which circuits are reinforced, and by how much.

- The largest environmental impacts occur in early childhood:

- Neurons are being formed (neurogenesis).

- Synaptic connections are established.

- Neural circuits are reinforced because of usage (apoptosis) or pruned because of disuse.

- And these circuits are myelinated which improves the speed of connection and communication.

- Brain plasticity is what gives us hope in resilience-building. Periods of rapid growth and reorganization offer great opportunity to adjust a child’s trajectory in a more positive direction through Positive Childhood Experiences. The brain is most plastic from birth to age 5, meaning that this is a crucial time to provide PCE’s.

- Bruce Perry MD, in his book, cowritten with Oprah Winfrey, What Happened To You states:

- Trauma within the first 2 years of life is more life-changing than trauma occurring later in life.

- Unfortunately, resilience-building is much more difficult in those kids/teens/adults who experience their trauma from age 0-2. ***

- Resilience-building is more likely to be successful for those who experience trauma later in life, even if the nurturing parent or adult is not ideal.

***Note from Dean: It is important to point out that evidence-based studies show that resilience-building CAN overcome trauma that occurs in the first two years. It is not hopeless!

Notes that summarize key points from Dr. Perry’s book.

Promoting Resilience

Definition of resilience: the ability to face a challenge, meet or overcome that challenge, and become stronger and not defeated by the challenge.

Resilience:

- A dynamic, evolving process that develops over time.

- Though rooted in innate, genetic potential, it is profoundly responsive to caregiving, culture, experiences, and other environmental influences.

- It can be taught and can be enhanced.

- Teaching resilience-building can build resilience in the teacher: providers, parents, and kids.

The most comprehensive review article on resilience is from Anne Masten: Resilience in Children: Developmental Perspectives. This comprehensive review of five decades of resilience research identified resilience factors that are common across cultures and countries.

Resilience Factors:

- Individual Characteristics: temperament, intelligence, attachment, self-regulation, optimism, hope, faith, strong sense of self, coping skills, motivation, problem solving.

- Positive Family Conditions: safe, stable responsive caregiver, family structure/cohesion, responsive and supportive parent-child interaction, stable and adequate income, stimulating environment.

- Community support: neighborhood safety, support services for needs, prevention and intervention programs, religious organizations, effective culture, economic opportunities for family, libraries, recreational facilities, and programs.

Implications for Pediatric Practices:

- Trauma-informed and resilience-informed practices are no longer asking the question “What is wrong with you?” and striving to fix the problem.

- Rather, we take on a partnering approach, recognizing the strengths and talents of caregivers and families.

- Nurturing the promotive and protective factors that build resilience (see below for link)

- Ameliorating the impact that trauma that has occurred. Asking the question, “What has happened to you and how can I help?”

Synopsis of two of the best review articles on resilience, and my comments on how MP and CHA are proceeding in response to these articles.

PCEs, BCEs and CounterACEs

ACEs is a concept that is becoming more well known as an individual, family, and public health concern. We are educating the public and our families with knowledge that trauma may impact their lives. ACEs screening will spread the word regarding the detrimental effects of toxic stress, but in addition, we can deliver the message of the beneficial effects of resilience-building.

Positive Childhood Experiences, PCEs, is an emerging buzz word in trauma and resilience circles. This is because of new research which is showing that the presences of PCEs may be more influential than the presence of ACEs. The following articles were published in the past 4 years. One coined the term PCEs. Another study looked at BCEs (Benevolent Childhood Experiences) and the third looked at CounterACEs. Though the terminology varied, these studied showed that positive experiences in a child’s life are more important to long term health than ACEs.

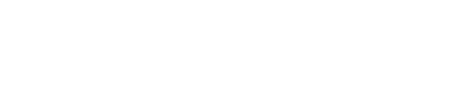

Bethell, JAMA Pediatrics, September 2019, Positive Childhood Experiences and Adult Mental and Behavioral Health.

- The author described 7 items as Positive Childhood Experiences and showed a dose-response relationship between PCE’s and mental/relational health.

- Note in the graphic below:

- Patients with 4-8 ACEs and 0-2 PCEs ~ 59.7% described poor mental health

- Patients with 4-8 ACEs and 6-7 PCEs ~ 20.7% described poor mental health

Benevolent Childhood Experience (BCEs) in Homeless Parents. Merrick, Narayan, Masten, J Fam Psychol. June 2019.

- A study of homeless parents surveyed for ACEs, BCEs, sociodemographic stress, and parenting stress.

- ACEs showed increased risk of stress as expected.

- BCEs showed lower odds of psychological stress.

Crandall et al, in October 2019, ACEs and CounterACEs: How Positive and Negative Childhood Experiences Influence Adult Health.

- The authors described PCE’s as “Counter-ACEs” using the BCEs scale.

- The findings suggest that CounterACEs protect against poor adult health and lead to better adult wellness.

The BCEs and PCEs questionnaires are now considered by experts in the field to standardized and validated queries. Higher scores are associated with stronger resilience.

Here is a Power Point discussing these articles in more detail, including the description of the life experiences that were defined as PCEs and BCEs, and the surveys used in these studies.

Note from Dean: It will be our goal to provide tangible interventions to build PCEs, BCEs and resilience in our families.

Attachment as a Foundational First Step for Resilience-Building

A secure attachment relationship with at least one safe, stable, nurturing caregiver (SSNC) over time enables the development of all the other resilience factors. In fact, without it, the others are very difficult to achieve.

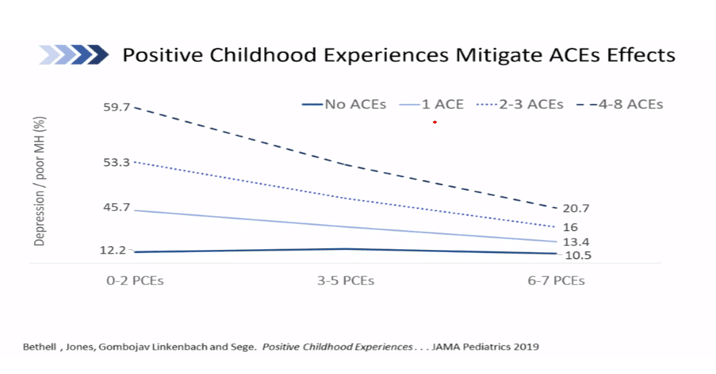

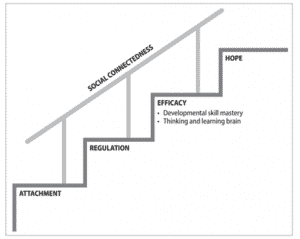

Think of resilience-building as a staircase. The foundational first step is attachment.

Resilience-Building:

- Attachment: a sense of security, trust in the caregiver, warmth, intimacy

- Regulation: self-control, soothing responses by the caregiver, co-regulation

- Efficacy: thinking and learning brain, development of skill mastery

- Hope: optimism

How Pediatricians Can Promote Secure Attachments

- Be a role model

- Model responsiveness, nurturing behavior, and safety – in words and actions.

- “Catch them being good”: Find parents’ strengths and reinforce them

- Be attuned to parents’ insecurities and worries.

- Show parents how to modulate their own emotional distress – which, in turn, teaches them how to help their child to do the same.

- Demonstrate empathy with attuned, attentive listening – show them how it is done.

- Validate how challenging parenting can be.

- Form a partnership with caregiver and child.

- We are the experts in pediatric knowledge, but THEY are the expert in their child and family.

- Learn from each other.

- Demonstrate confidence in a positive outcome – parents often fear the worst!

- Reinforce positive parenting.

** Reference: Childhood Trauma & Resilience. Heather Forkey, MD, Jessica Griffing PsyD, Moira Szilagyi, MD.

Attached (no pun intended) is an excellent article that gives a deeper dive into John Bowlby’s attachment theory.

How Do We Assess Positive Childhood Experiences?

Healthy Outcomes from Positive Experiences (HOPE) is an organization based out of Tufts University. Their mission is to

“Demonstrate the formative role of positive experiences in human development, seek to inspire a HOPE-informed movement that fundamentally transforms how we advance health and well-being for our children, families and communities.”

From the HOPE website: “While there is not a single, evidence-based approach providers can use to ask about positive childhood experiences, the following options represent research-informed methods currently being used in the field. The first two techniques are based on standardized, validated queries and will generate scores. Higher scores are associated with higher resilience. The next two are more conversational. They serve to better understand the child and family circumstances while forming a foundation for engaged collaborative problem solving.

The four assessments of positive childhood experiences are:

- Positive Childhood Experiences Scale.

- Benevolent Childhood Experiences Scale.

- The Four Building Blocks of Hope, developed by Gretchen Pianka, MD.

- Narrative Therapy Techniques.

The HOPE website is: https://positiveexperience.org/

The attachment today is a 2-page article which discusses the above four ways to assess PCE’s:

Positive Parenting builds Resilience and Social-Emotional Development

A pediatrician’s role is to be intentional in our approach, to help parents be the best caregivers they can be.

- Understand your families: listen first.

- Gradually guide your families over time.

Some parents are “naturals” at parenting because they were raised by caregivers who modeled positive parenting skills and had a flexible, responsive parenting style. At the other end of the spectrum are caregivers who are living in poverty with multiple stressors related to finances, housing, neighborhood violence, and food insecurity may face immense challenges that can affect their parenting.

Outline of how pediatricians can build positive parenting gradually over time.

- Find out what caregivers bring to parenting. What are their strengths? What are their challenges?

- Observe them in the room.

- What is their background?

- Ask one of these questions:

- Are you planning on raising your child like how you were raised?

- Are there things about how you were raised that you would like to avoid?

- Are all caregivers on the same page about raising your child?

- What are your goals for your child? (Write the answers down and review at later visits)

- If parents have experienced trauma or challenges remember your trauma-informed care approach:

- Demonstrate empathy

- Engage with them nonjudgmentally

- Let them know that you will be with them on this journey the entire time.

- Parenting styles can vary *** (authoritative, authoritarian, permissive, uninvolved) but keep to routines.

- Daily routines are reassuring for kids.

- When parents try a new parenting strategy (because of challenging behavior) it is important to point out that behaviors may escalate before they improve. The escalation should subside over 1-2 weeks. This is normal.

- Remind caregivers that we all tend to revert to familiar parenting patterns when we are stressed.

- Learn their history – especially that of trauma.

- Break down parenting skills into smaller chunks so that they can enjoy small successes.

- Stay positive and keep encouraging them in the process.

- Role model:

- Attuned, attentive listening

- Offer specific praise focused on certain characteristics.

- Understand the child’s point of view and value it.

- Assume that the child is doing their best.

- Give clear expectations and boundaries and utilize empathy and compassion.

- Emphasize teaching rather than controlling the child’s behavior.

- Start early in childhood to establish routines.

- Predictable soothing bedtime: e.g., bath, brush, book, bed.

- Allow for some flexibility when necessary and teach your child how to adjust to change.

** Reference: Childhood Trauma & Resilience. Heather Forkey, MD, Jessica Griffing PsyD, Moira Szilagyi, MD.

*** Here is the reference to an article which does an excellent job of discussing parenting styles:

Positive Parenting Tool: Special Time **

- This exercise is for 2–5-year-olds but can be modified for all ages through adolescence.

- Special time is a time for a parent to connect with a child. It builds on their relationship and will help inform all parenting – and make it easier.

- Special time should not be structured or involve any screens.

- The child chooses the activity or if not, they sit together and see what happens.

- Follow the child’s lead. It could be a game of chase or maybe just snuggling; other times it could be playing pretend or building a fort.

- A few key things: 10 minutes a day or at least on a weekly schedule (3 x a week).

- Turn off all phones and distractions (care for other children).

- Let the child choose an activity but it should be unstructured without rules if possible.

- The parent should not instruct or ask questions. Follow the child. They are in charge.

- Call it your child’s name time “Annie’s Time”

- Make sure other siblings are not present or otherwise occupied (book on tape with headphones or with other parents).

- Have a schedule so each child will have special time of their own.

- In working with families, you will need to have some answers to the questions and issues that come up with this, but it is so easy to teach and works. Parents and children love it. Consider modeling it for parents who may struggle with it.

- The negative behavior of some children is often just a reflection of their desire to get their parent’s attention. Special Time can alleviate much of this negative attention-seeking by giving them the positive attention that they really need.

Attached is a handout can be used to encourage Positive Parenting :Positive Parenting Handout

Building Social Emotional Development and Resilience in Young Children

- Metropolitan Pediatrics and the Children’s Health Alliance have been engaging in trauma-informed care (which we have called compassion-informed care) and resilience-building interventions since 2016. Since the start of this program, the state of Oregon and the Oregon Health Authority have placed an emphasis on Social Emotional Development and Kindergarten Readiness. Nationally, there is momentum to build these features through Early Relational Health.

Though the terminology may vary, the features of all these programs are interrelated and more similar than different.

Recall from a previous email the stairstep model of resilience-building**. The four steps in that model included attachment, regulation, self-efficacy, and hope.

The model for Social Emotional Development is very similar.

Definition: Social-emotional development is a child’s ability to understand the feelings of others, control their own feelings and behaviors, and get along with peers.

Three features of Social Emotional Development are:

- Attachment

- Initiative

- Self-Regulation

Note from Dean: Attached is a Power Point which discusses features of Social Emotional Development and how it compares to Resilience Building. This PP was for a talk that I was preparing prior to Covid. In-office interventions are presented in the Power Point to help families build resilience and Social Emotional Development. Many of these interventions are things that pediatricians already talk about, but now can be contextualized for resilience-building and SED.

Link: Social Emotional Development

** Reference: Childhood Trauma & Resilience. Heather Forkey, MD, Jessica Griffing PsyD, Moira Szilagyi, MD.

Cultural Connections: Becoming Culturally Informed

Family history, social context and culture are woven together to the fabric of families’ experience and resilience. Culture provides context, frame of reference, and support for relationships. It is the lens through which we make sense of the world.

Trauma and relationships are intertwined. Trauma can disrupt relationships. Culture can help rebuild cohesion when relationships and meaning are shattered by trauma.

Incorporating a culturally informed approach will augment our effectiveness as pediatricians because all relationships are immersed in a culture.

From Chapter 5 of Childhood Trauma and Resilience.

FABRIC: The context in which a child builds resilience and/or experiences trauma

- FAmily

- How was the parent raised?

- How does the caregiver’s history inform their parenting?

- Are there intergenerational trauma considerations?

- BRoader social context

- What are the current stressors for this caregiver or family?

- Consider social determinants of health: poverty, housing, food insecurity, safety of the community.

- Cultural considerations

- Race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, immigration status, foster care

- Is there trauma, and if so, how can we help?

** Reference: Childhood Trauma & Resilience. Heather Forkey, MD, Jessica Griffing PsyD, Moira Szilagyi, MD.

This week’s attachment expands on the discussion of culture, and how we as providers can become more culturally informed.

Brain Changes and Behavior Changes from Traumatic Stress

Neuroimaging from fMRI and PET scanning has shown certain neuropathic changes that have been associated with traumatic stress. This includes diminished left brain (verbal) function, smaller corpus callosum, smaller hippocampus by volume, hyperreactive amygdala and disorganized temporal lobe function. The specific behaviors resulting from these changes are discussed in the attached Power Point.

A simple summary of trauma symptoms is represented by the mnemonic FRAYED. **

** From Trauma & Childhood Resilience. Heather Forkey, MD, Jessica Griffing PsyD, Moira Szilagyi, MD.

Note from Dean: This week’s attachment is excerpted from a PowerPoint which further elucidates the pathophysiology of complex trauma, traumatic stress, and how these changes affect behavior. Consider this a quick refresher course in trauma-informed care and why we need it.

Trauma Pathophysiology: Spectrum of Behavioral Symptoms

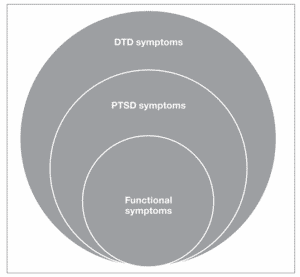

The clinical symptoms of trauma in childhood can present along a spectrum from mild symptoms to more severe ones

Asymptomatic: Many children who have experienced adversity of trauma may have no symptoms and it is only through disclosure from the child or caregiver that we may learn of the event. In many of these situations the caregiver and other support has provided adequate buffering and the child has adapted well. The child may be at higher risk of long-term poor outcome however, so surveillance is recommended.

Functional symptoms are usually short-term disruptions of daily function (sleep, eating, elimination, behavior). Brainstem and lower order brain functions are often the first to be affected by trauma. These disruptions of homeostasis can usually be overcome with reassurance, return to predictable routines, and the support of a caregiver who is present and attuned to the child’s needs and thus helps dampen the child’s stress response and promotes resilience.

PTSD, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, is defined by a cluster of symptoms following a traumatic event or experience, which last longer than 1 month and affects the child’s functioning:

- Intrusive symptoms: thoughts, nightmares, flashbacks

- Avoidance: feeling numb, refusing to talk about the event

- Negative alterations in cognition or mood

- Alterations in arousal or reactivity: hyperarousal, irritability, exaggerated startle, sleep or concentration problems.

- Dissociation: feeling detached from oneself, feeling as if things are not real

DTD is Development Trauma Disorder is a proposed diagnosis of complex trauma in children based on evidence that children exposed to multiple, severe, or prolonged traumas are at risk for severe disruptions in their development in the domains of emotional health, physical health, attention, cognition, learning, behavior, interpersonal relationships, and sense of self. DTD symptoms overlap with PTSD symptoms, but DTD includes a broader spectrum of dysregulation taking into consideration that the type, severity, and timing of trauma are significant because the impacts on multiple areas of the rapidly maturing brain vary with development age and stage of the child. DTD is not in the DSM-5 but is commonly used by experts in child trauma.

** Reference: Childhood Trauma & Resilience. Heather Forkey, MD, Jessica Griffing PsyD, Moira Szilagyi, MD.

Attached is a table that comprehensively lists potential symptoms of trauma by age groups:

Nature Therapy

As pediatric providers, we know how to recognize and diagnose mental and behavioral health issues. We have been trained in pharmaceutical options that can be prescribed for anxiety, depression, or hyperactivity. Most of us have a network of mental health providers that we rely on to provide counseling, though this option is becoming more and more difficult to access due to the decreasing availability of providers. Physicians within the Children’s Health Alliance have learned the science showing the benefits of resilience and are practicing evidence-based interventions to build resilience, improve connections, and decrease anxiety or depression.

In addition to these therapies, I’d like to offer therapeutic options which I use daily as a prescription for anxiety, depression, and stress. They are simple to recommend, relatively easy for families to agree to, and have the scientific evidence for proven benefits. Each can be used prescriptively as a treatment for patients who are suffering from mental health problems and can also be used preventively to immunize against future stress.

Nature Therapy

Nature Therapy describes an intervention that encourages meaningful exposure to nature which research has shown to provide benefits for physical and mental health.

Theories on why time in nature improves our health:

- Time or restoration therapy. Time in stressful environments, including crowds, noise, and traffic, tires our concentration or attention, which increases fatigue and irritability. Time in nature provides a softer fascination, interesting but not fatiguing, which provides restoration of our energy and attention, reducing our stress and irritability.

- Stress reduction theory. After spending time in a stress-filled environment, spending time in nature provides faster recovery from stress and irritability.

Benefits of Nature Therapy from 2018 Meta-Analysis study: **

- Improved mental health was shown for stress, anxiety, and depression

- Improved medical health was shown in diabetes, hypertension, birth outcomes, and ADHD.

** from 2018 meta-analysis of research on nature therapy:

A Prescription that is easy to prescribe, relatively easy to follow through on, and backed up with evidence-based research:

- Spend at least two hours in nature each week, at least 20 minutes each time.

As physicians, we can problem-solve with families on how to accomplish this. Don’t forget to follow up with them to encourage compliance. The definition of what “nature” is, is self-defined. If one feels that they have had a meaningful nature experience in their neighborhood, in their garden, or a park, they can reap the benefits of nature therapy. Emphasize that this is a prescription for life and will continue to provide the benefits over years.

“Green Space” Therapy: Brief Interventions in Nature Therapy

- “Forest Bathing”. Brief trips or easy hikes. Unstructured exploration of the environment. Slow down and notice with all your senses: see the beauty, smell the odors, hear the sounds, etc.

- Animal therapy. Spending quality time with animals is relaxing, and often provides exercise for both. Pets show their unconditional love and devotion to you. Caring for an animal teaches responsibility, empathy, and opportunities to show love physically.

- Nature arts and crafts. Create works of art using natural materials: leaves, twigs, and rocks. Linger while you collect them and note their natural beauty.

- Have a campout in your backyard.

Here is an article from Web MD on Green Space therapy

https://www.webmd.com/mental-health/news/20190225/green-space-good-for-your-childs-mental-health

Blue Space Therapy: Therapy from Bodies of Water

Research has shown that people who spend extended time around natural bodies of water (ponds, rivers, streams, lakes, ocean) show improved mental health. Though the research is newer and less developed, the results are still compelling.

Some of the theories on why being around natural bodies of water provide psychological benefits.

- Same benefits as listed above from green spaces.

- Being near water encourages more exercise.

- Water provides a visually changing environment. Reflection of the light varies which allows people to ruminate less on stressors and encourages more mindful appreciation of the senses provided: waves, ripples, sounds of water movement, etc.

- Audio stimulation from the sounds of water is relaxing.

- Many water environments encourage the gathering of friends and family, which invites improved connection.

- Along the color spectrum, blue is associated with peace and tranquility.

Resilience-Building: Nature therapy builds COPING and CONNECTION

Quite obviously, nature therapy can be a valuable tool in learning how to cope with stress. It can be used therapeutically, after a difficult day, or preventively building resilience for future stress. In addition, nature can be a builder of connections with others. Finding friends or family to experience nature with provides two resilience-building benefits in a relatively brief amount of time.

Here are two articles discussing some of the research on Blue Space Therapy

https://www.onlinepersonalitytests.org/blue-space-therapeutic-mental-health-benefits/

Gratitude Exercise #1: Three Roses and a Thorn

At the end of the day, perhaps at dinner or at bedtime, parents discuss with their kids the best parts of the day and the most challenging. Parents provide a role model in how they assess their day.

Three Roses: My favorite part of the day.

We recommend three roses to create a positive mindset, but there is no limit.

Thorn: The most challenging part of the day.

Discussing the thorns provides insights for parents into what their child worries about during the day. It provided rich discussions for possibilities in problem-solving. Allow them to identify their challenge, discuss various options to address it, and help them to come up with a possible solution.

Gratitude Exercise #2: Three Good Things

One of the earliest proponents of gratitude was Martin Seligman Ph.D., considered by many to be the father of positive psychology, and a pioneer in resilience research.

The following simple exercise in gratitude building has been described as the “most successful technique for long-term happiness.” It almost sounds too easy to be true. Try it out for yourself, your partner, and your child.

3 Good Things*

Every night for the next week, set aside ten minutes before you go to sleep.

- Write down three things that went well today and why they went well. You may use a journal or your computer to write about the events, but you must have a physical record of what you wrote. The three things need not be earthshaking in importance (“My husband picked up my favorite ice cream for dessert on the way home from work today”), but they can be important (“My sister just gave birth to a healthy baby boy”).

- Next to each positive event, answer the question “Why did this happen?” For example, if you wrote that your husband picked up ice cream, write “because my husband is thoughtful sometimes” or “because I remembered to call him from work and remind him to stop by the grocery store.” Or if you wrote, “My sister just gave birth to a healthy baby boy,” you might pick as the cause “God was looking out for her”.

- Writing about why the positive events in your life happened may seem awkward at first, but please stick with it for one week. It will get easier. The odds are that you will be less depressed, happier, and addicted to this exercise six months from now.

* From “Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being.

By Martin Seligman, Ph.D.

The evidence for the benefits of gratitude is vast:

This article is one that summarizes the literature well:

https://www.mindful.org/the-science-of-gratitude/

This article reviews the science of gratitude in adults:

https://positivepsychology.com/benefits-of-gratitude/

This article lists some of the more popular gratitude exercises:

Addressing Trauma. First Response: SPLINT

Addressing trauma need not differ from that of other pediatric concerns. Identify the issue, validate the parents’ concerns, triage for urgency, determine follow up care and coordinating the care team.

In medical settings we need efficient ways to address health concerns during a busy office day. Like a physical injury, we efficiently collect a history, do a physical exam, explain our assessment, then stabilize and provide pain management. In other words, we SPLINT the problem. This acronym serves as a guide in our approach to the management of trauma.

Saying that trauma/stress may be the cause.

State that trauma is one consideration of the cause of the problem and that further exploration is needed.

Problem-solve with the family

What is the most distressing part of the concern and what should be addressed first? Ask what strategies have been tried and whether they were successful. Prioritize. Consider asking how people from the family’s culture usually respond to the concern in question.

Language

Provide vocabulary for the child and family to talk about the concern. Give the child words for what they may be feeling (scared, angry, sad, worried). Remind parents that behavior is often the tip of the iceberg. What shows up as anger or opposition overtly may be a child’s way of coping with the feelings beneath the surface (grief, fear, jealous, shame, etc.).

Investigate further

What can we do to understand the concern better, provide safety, determine urgency, and respond well? More information may need to be gathered later privately in another room or by phone. It may be necessary to speak to the child in private. Assess safety including risk of suicide.

Normalize

Explain to the caregiver that the child is having a normal reaction to an abnormal set of circumstances. Children will often think of themselves at being injured or as having something “wrong with them”. Switch the language to make it clear that “it’s not what’s wrong with you; it’s what happened to you”.

Therapy

Reassure the child and family that we have good treatment available, we will be with them through the journey, and we can be confident in recovery.

The Invisible Suitcase is a conceptual tool that helps children and families understand the effects of trauma. It was developed to assist foster families caring for traumatized children and is an excellent teaching tool to normalize and understand the secondary behaviors that arise from deep troubling emotions.

- The Invisible Suitcase, as developed for foster parents, by the National Child Traumatic Stress Network, is available here: https://www.complextrauma.ca/wp-content/uploads/P4-The-Invisible-Suitcase.pdf

- The Invisible Suitcase, presented in an animated form, developed by Child Bereavement UK is available here:

https://smileymovement.org/single-award/88

** Reference: Childhood Trauma & Resilience. Heather Forkey, MD, Jessica Griffing PsyD, Moira Szilagyi, MD.

The Intersection of Culture and Trauma

Building on the clinical symptoms of trauma, we will now consider how culture may affect the traumatic experiences of individuals and populations. Trauma is the experience of a real or perceived threat to one’s life or safety, or of that of a loved one. Trauma and culture are entwined in the thoughts and behaviors of the children and families that we serve and in our own thoughts and behaviors. It is important that pediatricians address the culture-specific dimensions of children’s and caregivers’ trauma and assess stressors within their sociopolitical context. For example, LGBTQ people have higher exposure to experiences that contribute to trauma than heterosexual individuals, including higher rates of exposure to experiences that result in traumatic stress (e.g., family or peer rejection).

The same traumatic event may be perceived differently by various individuals who experience it, even if they are from the same culture. Scholars examining trauma responses across cultures have found a wide range of emotional and behavioral responses to similar traumatic events. Trauma can also affect and disrupt an entire community or culture, even extending its effects to future generations.

Some definitions:

Historical trauma. Cumulative emotional and psychological wounding due to collective trauma experienced by a group of people who identify with each other. This trauma occurs over time, affecting multiple generations. Examples include genocide, slavery, forced relocation, and prohibition of spiritual or religious practices that affect a population.

Intergenerational trauma. This differs from historical trauma. This refers to the specific experience of trauma across familial generations but does not necessarily include a shared group. Examples include child abuse or sexual abuse which may affect one family, but not necessarily affect people beyond that family.

Racial trauma refers to exposure to dangerous events and stressful impact by real or perceived racism. In the United States, Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, Hispanic/Latino, Asian American, and other children of color experience race-based traumatic stress, with Black children having significantly more exposure to racial discrimination than other groups.

Microaggressions. These are everyday small, subtle occurrences of discrimination or racism. These minor episodes, when accumulated over time can add up to causing significant traumatic stress.

** Reference: Childhood Trauma & Resilience. Heather Forkey, MD, Jessica Griffing PsyD, Moira Szilagyi, MD.

Note from Dean: This Chapter from Childhood Trauma and Resilience includes some excellent and very timely information which is attached to this email. Topics include the following:

- Common Traumatic Stress Reactions in Response to Racial Trauma

- Subtle but pervasive threats or microaggressions that can trigger traumatic stress

- Strategies to build trust

- Comparison of the terms: Multicultural, Social Justice and Culturally Responsive.

Helping Stressed Parents to Self-Regulate

The ability of a parent or caregiver to mediate and buffer a child’s experiences and provide a safe, secure, and nurturing relationship is the most crucial in developing resilience in a child – whether there has been trauma in the past or not. Thus, it is equally crucial that the caregiver can self-regulate their own emotions and behavior.

Here are some circumstances that might pose challenges to a caregiver’s ability to self-regulate:

- Trauma in the caregiver’s history

- Behavioral challenges that traumatized child pose

- Overly permissive or overly protective parenting styles

- Inappropriate blame: blaming the child or blaming the caregiver for the trauma

- Minimizing or denial of the child’s trauma experience

How pediatricians can help caregivers:

- Let the caregiver know that they are in a safe place. Use a calm tone, relaxed demeanor, with humor.

- Normalize their emotions. Having negative emotions is typical and not wrong. Ask them to name their emotions and validate them.

- Be available. Be predictable and reliably compassionate.

- Give them the space to share their thoughts and feelings.

- Let them know that you will be with them on this journey. Your “presence” is more important than your words.

This week’s attachment gives even more ways pediatricians can support parents and caregivers under stress.

Helping Stressed Parents to Self Regulate

** Reference: Childhood Trauma & Resilience. Heather Forkey, MD, Jessica Griffing PsyD, Moira Szilagyi, MD.

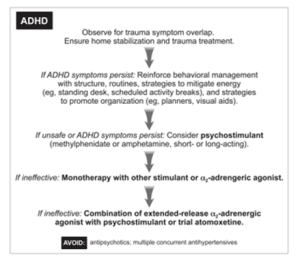

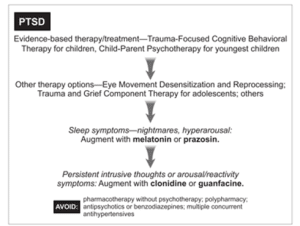

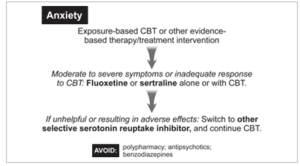

The Role of Medication in Treating Children Exposed to Trauma

As we have discovered, the most appropriate interventions for children who experienced trauma are:

- Support safe, stable, and nurturing relationships

- Guidance of positive parenting

- Evidence-based trauma therapy

Yet pediatric providers are often called on to address the symptoms of trauma with medication. Fortunately, the AAP and AACAP have provided recommendations to guide us.

Considerations:

- The overlap of trauma-related symptoms with ADD, ODD, and mood disorders may confound the diagnosis.

- Populations with inconsistent health care and history may lead to misdiagnoses.

- Response to medications from trauma survivors may be unpredictable.

Stepwise approach to treating ADHD in children exposed to trauma (from the AAP)

Stepwise approach to treating PTSD in children exposed to trauma (from the AAP)

Stepwise approach to treating ANXIETY in children exposed to trauma (from the AAP)

Stepwise approach to treating DEPRESSION in children exposed to trauma (from the AAP)

**Childhood Trauma & Resilience. Heather Forkey, MD, Jessica Griffing PsyD, Moira Szilagyi, MD

Surveillance and Screening: Recommendations

As a review from last week, the context in which we inquire about or screen for trauma is very important, since physical and psychological safety is crucial; the ideal context may be the family-centered pediatric medical home.

When engaging in surveillance or screening for trauma, it is imperative that all pediatric providers and personnel consider the following. This is the foundation for trauma-informed care.

- Create an environment that provides emotional and physical safety for children and families.

- Educate and train all personnel in trauma-informed care.

- Prepare providers and all office personnel to notice, identify, and approach issues around childhood trauma and respond to them in ways that promote resilience, recovery, and healing.

- Have a variety of in-office trauma-informed care resources available.

- Create a network of community resources demonstrated to reduce stressors on families and thus reduce symptoms in children and caregivers.

- Offer in-office assistance or referrals for community-based mental health resources for trauma-informed care.

- Use strategies to build the resilience of personnel and reduce the impact of secondary traumatic stress on them.

Questions and Answers

Q: When will we be ready?

A: Surveillance and Screening done by practices must be preceded by practice readiness. This is why we are providing this trauma-informed care training.

Q: What are the risks?

A: Conversations of trauma have the potential, though infrequent, to trigger shame in those we are speaking with. Shame is a powerful emotion and not one that is conducive to healthy discussions promoting resilience and recovery. Relationships must be the primary focus: between provider and family, and between parents and child. These relationships provide the foundation for which resilience is built and where recovery must occur. Review the previous discussion on Engagement to facilitate these relationships.

Q: What if we uncover trauma?

A: Anticipate this. Consider what our practices and community have to offer, including but not limited to: resilience-building tools, psychoeducation, referrals for community services or mental health. Close follow up is needed. More to come in later emails.

Q: What questions can I ask for surveillance of trauma?

A: See the attached document

Q: What tools can I use to screen for trauma?

A: See below

Trauma Surveillance Questions for providers:

These are questions that providers can ask to uncover trauma exposure. These questions are from the textbook Pediatric Trauma and Resilience by Heather Forkey, MD, Jessica Griffin PsyD and Moira Szilagyi, MD.

- Has anything bad, sad, or scary happened to you since your last visit?

- Are planning on raising your child the same way you were raised?

- Do you and your partner agree on parenting and how to discipline your child?

- How does your child handle stress?

- I can see how much you love your child, but parenting can be both joyful and stressful. What brings you joy? What causes you stress?

- Who supports you with raising your child/children?

- Are there any behavioral problems with your child at home or at school?

- Have there been any dramatic changes in your child’s mood or personality?

- Has anyone gone or come from the household lately?

- Have there been any problems with sleep or enuresis?

- Has your child ever witnessed anyone being harmed at home or in the community?

The AAP has suggested framing questions about harm in the context of the symptoms noted:

- The behaviors you describe and the trouble she is having with school and learning are often warning signs that the brain is trying to manage stress or threat. Sometimes children respond this way if they are being harmed, or if they saw others they care about being harmed. Do you know if your child saw or witnessed violence at school, with friends, or at home?

Reference: Childhood Trauma & Resilience. Heather Forkey, MD, Jessica Griffing PsyD, Moira Szilagyi, MD.